How to Think When Writing Good Issues¶

Glossary¶

Issue A written report or request (e.g., in GitLab/GitHub) describing a problem, task, or feature.

Bug report A detailed record of a problem found in software, created to help developers fix the issue.

Preconditions Everything that must already be true before reproducing a bug - such as logged-in state, selected data, or previous actions.

Dependency A package, library, or external component the system relies on.

Edge Case A situation that occurs at the extreme or boundary of normal operation and may trigger unexpected behavior.

Acceptance Criteria Clear conditions that define what "done" means and how the team can verify the feature works as intended.

Writing an issue is like leaving instructions for someone who has never seen your laptop, your tabs, or your “creative” folder structure. The reader only has what you write — nothing more. If they understand the problem or idea right away, great. If not, they’ll come back with questions you secretly wish you had answered from the start.

Quote

A good issue removes guesswork.

A vague issue creates side-quests nobody asked for.

Why Mindset Matters¶

An issue is a small story: something happened, or something should happen, and you want the next person to see it the way you saw it. No puzzles, no hidden clues. When issues are clear, teamwork feels smooth. When they're not, people spend more time interpreting than building.

When writing an issue, remember that other people do not think with your mind, do not work on your machine, and do not carry your assumptions. What feels “obvious” to you may be invisible to someone else. A teammate might read your issue after a long day, on a different device, or with a completely different mental model of the system. Clarity is an act of kindness.

Example: The Trivial Step That Isn’t

You write: “Open the project and run it.” Your teammate wonders: Which branch? With or without the test data? Using the script or the IDE? They try three combinations before the bug appears. For you, it was one step. For them, it was a puzzle.

Never assume your environment is the same as theirs. What works flawlessly on your laptop might break instantly on someone else’s. Different operating systems, browser versions, dependencies, configs — even a single missing package can turn a “simple instruction” into an afternoon of debugging.

Example: The Environment Surprise

On your machine: “The login works fine.” On theirs: “I can’t even start the app.” Turns out you installed a global dependency months ago and forgot it existed. Not their fault. Not your fault. Just reality.

And finally: your way of doing something is not the only way — and not automatically the “right” or “best” way. Everyone makes mistakes, including you. The more gently you acknowledge that possibility, the easier collaboration becomes.

Example: The Humble Assumption

Instead of “This endpoint is definitely broken,” try “It seems this endpoint might respond differently than I expected — here’s what I saw.” This leaves space for learning, correction, and shared insight.

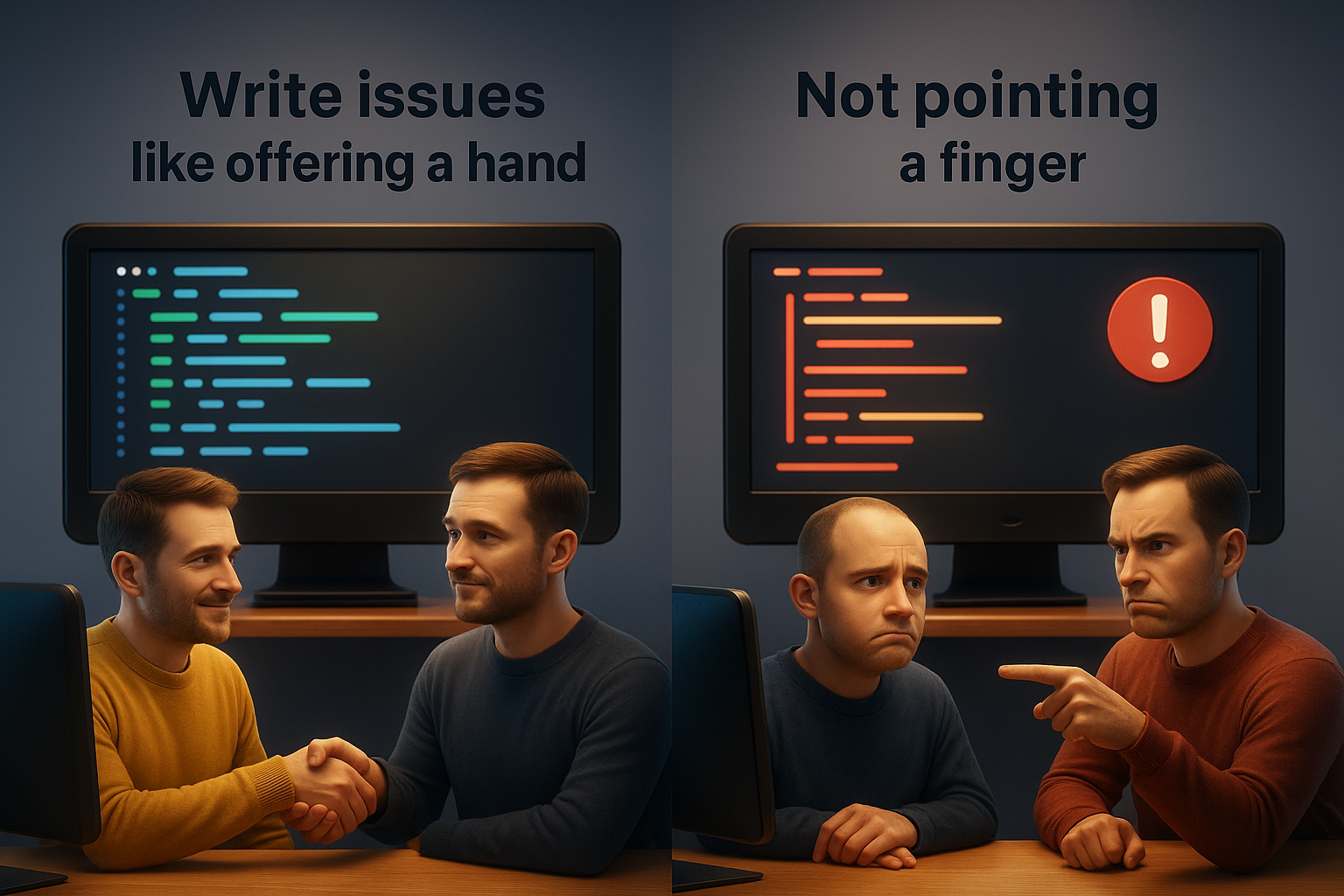

Treat issue writing like offering a hand, not pointing a finger. You guide others through your experience, step by step, knowing that their path may look different. This mindset reduces frustration, builds trust, and makes teamwork feel lighter — for everyone involved, including you.

The Mindset on the Receiving Side¶

Writing good issues matters — but reading them well is just as important. Every issue is a tiny window into someone else’s experience, and it’s surprisingly easy to misread what you see through it. When an issue touches code you wrote, a workflow you designed, or a decision you defended, it can feel personal even when it isn’t. That’s normal: humans bond with what they create. We see our work as extensions of ourselves. But in a team, that instinct can quietly distort collaboration if we’re not aware of it.

When someone reports a bug in your code, it is not an attack on your abilities. They are not judging your worth or your intelligence. They’re simply describing what happened on their screen. Bugs appear for dozens of reasons — timing issues, edge cases, environment differences, missing assumptions, misunderstandings, or things nobody expected. Treating them as personal failures only makes the work heavier. Treating them as shared puzzles makes the work lighter.

Similarly, when reading feature requests, be careful not to slip into a posture of “I know better.” Expertise is valuable, but expertise can be a trap when it turns into gatekeeping. The person writing the issue sees a corner of the system you do not. They experience the product differently. They might notice friction you learned to ignore long ago. Reading their request with curiosity — not defensiveness — uncovers blind spots and helps everyone see the project more fully. Expertise is strongest when it listens first and speaks second.

Sometimes issues will be messy, incomplete, or written in a rush. Resist the urge to roll your eyes or assume incompetence. People write issues under all kinds of conditions: late at night, after a confusing crash, during a stressful sprint, between classes, or while juggling responsibilities. A clarifying question asked with softness goes much further than a sharp correction. And, in a subtle way, you teach others how to write better issues simply by how respectfully you respond.

Also remember that an issue is never the whole story. A terse sentence could hide 20 minutes of frustration. A clumsy explanation may reflect someone’s uncertainty, not their carelessness. Humans communicate imperfectly even with their best effort; technology adds another layer of misinterpretation on top. Reading issues generously — assuming the sender had good intentions — prevents spirals of misunderstanding that drain energy and trust.

Finally, approach every issue, bug or feature request, with the assumption that you, too, can make mistakes. Everyone does. Even experts misread scenarios, forget edge cases, or design features that confuse real users. When you stay open to correction, you signal psychological safety: it’s okay to be wrong, it’s okay to ask, it’s okay to improve. This attitude spreads quickly. Teams that embrace it become more resilient, more collaborative, and far more effective than any collection of “experts” defending their turf.

The way you read issues shapes the way people write them. If you respond with curiosity instead of defensiveness, if you treat reports as gifts instead of annoyances, if you see requesters as teammates rather than critics, your project becomes a place where people feel safe to speak up. And that — more than any template — is what keeps a team healthy.

Bug Reports: Make the Bug Appear on Command¶

Bug reports are not complaints. They are instructions for making something go wrong — on purpose.

If your steps reliably summon the bug, the report works.

A bug is a mismatch

Expected behavior and actual behavior do not match.

When you write a bug report, the first thing you offer the reader is a sense of place. A bug does not exist in the abstract — it lives in a specific environment: a device, an operating system, a browser version, a branch, a particular configuration. Leaving these out is like dropping someone in a foreign city and telling them to “just walk to the café.” Even small differences can completely change what they see. On your machine the feature might work flawlessly because you installed something months ago and forgot; on theirs, the same feature collapses instantly. Giving a clear description of the environment removes invisible variables and prevents the reader from building the wrong mental picture. Psychologically, this matters because human minds fill gaps automatically; if you don’t give context, people assume their own — and assumptions diverge quickly.

Just as important as the environment are the preconditions: everything that was already true before you interacted with the feature. Logged-in state, selected item, the presence of sample data, previous actions — these seemingly tiny moments often carry the clue to why the bug appears. Our brains naturally compress repeated tasks into muscle memory, so we stop noticing them. But someone else following your instructions without those hidden steps will end up in a different state and never reach the bug. By explicitly stating the preconditions, you help others reconstruct the same setup and avoid the frustration of chasing a bug that only exists because something “obvious” wasn’t actually obvious.

From there, the heart of the report is the sequence of steps that make the bug appear. These steps should be so clear that someone could follow them half-asleep and still get the same result. Not because your teammates are half-asleep (hopefully), but because predictability matters more than elegance. A repeatable sequence turns a mysterious glitch into a reproducible phenomenon that can be tested, explored, and eventually fixed. When steps are vague — “open the thing and try it” — the reader is forced to make guesses. And guesses multiply. One guess leads to another, until you both think you're talking about the same action but you’re actually several branches apart. Reliable steps prevent that slow divergence.

With that setup ready, you can explain the core of the issue: the expected result versus the actual result. These two small descriptions form the anchor of the entire report. They define the gap between intention and reality — the moment where the system’s behavior surprised you. Humans understand problems best when contrast is clear, and stating “what should have happened” next to “what actually happened” sharpens the contrast. Without this, the report risks becoming a vague story rather than a specific mismatch. The clearer the gap, the easier it is for the reader to investigate or validate a fix later.

To support all of this, adding evidence — screenshots, logs, video clips — provides something concrete to look at. Visual or textual evidence stops misunderstandings before they start. People interpret language differently, but everyone interprets a screenshot the same way. Evidence is the antidote to miscommunication: it locks the interpretation of the problem to something objective. It also reduces the cognitive load on the reader; they don’t have to imagine what you saw — they can see it themselves.

Finally, one of the easiest traps to fall into is trying to diagnose the problem while reporting it. Humans are pattern-seeking creatures; when we see something odd, our minds jump to explanations. “The backend must be failing,” “the database didn’t update,” “this line of code is probably wrong.” These guesses often feel helpful, but they can nudge the reader down the wrong path before they even begin. A teammate who trusts your guess may spend an hour searching in the wrong subsystem. More subtly, offering explanations can create a psychological undercurrent of blame — even unintentionally — which makes collaboration feel heavier. By focusing on what you observed, rather than why you think it happened, you leave space for the assignee to explore possibilities freely and professionally.

In the end, these principles matter because they protect shared understanding. They counteract the habits our brains naturally rely on — skipping details, assuming similarities, filling in gaps, and jumping to conclusions. Writing a clear issue is not just a technical task; it is an act of cognitive empathy. You help someone else see what you saw, without the shortcuts your mind took along the way.

Feature Requests: Describe a Future That Makes Sense¶

Feature requests describe something that should exist, not a wish list entry.

A good request explains why the feature matters, who needs it, and what the outcome should look like.

When you write a feature request, the very first thing to clarify is why the feature matters at all. Every new idea begins with some small irritation or limitation: a task that takes too long, information that’s hard to find, a workflow that feels clumsy. These little moments are where real value hides. If you cannot name the specific frustration the feature solves, it becomes difficult for others to understand its purpose. Teams naturally prioritize what relieves pain, not what simply “sounds nice.” Psychologically, people are more motivated by fixing a shared inconvenience than by following abstract visions. Starting with the motivation aligns everyone around a concrete reason to care.

Once the motivation is clear, describing the use case grounds the request in reality. A feature becomes meaningful when you show exactly when a user would reach for it: during a workflow, at the end of a task, while navigating a page, or when something unexpected happens. A simple scenario — “Students exporting their results to share with a partner” — is far more powerful than a broad statement like “Users want more export options.” Our brains latch onto stories far more easily than concepts. A clear, human-scale example helps teammates imagine the moment the feature becomes useful, which in turn shapes better design and more thoughtful implementation.

After you’ve framed the scenario, the next step is to describe what users should be able to do, rather than how developers should build it. This is one of the most common pitfalls: people tend to leap straight from idea to implementation, sketching button shapes or naming database fields as if construction details were the essence of the request. But focusing on user behavior broadens the solution space, allowing developers, designers, and testers to bring their expertise to the table. It keeps the feature flexible rather than locking the team into a single technical path. Psychologically, this lowers friction; instead of telling teammates what to build, you give them the freedom to determine how best to build it.

Exploring alternatives is another subtle but important step. By naming the other options you considered, you demonstrate that the feature wasn’t chosen impulsively. This builds trust: teammates see that you’ve thought through the problem instead of grabbing the first idea that came to mind. Listing alternatives also reveals hidden constraints — things you tried, things you rejected, and why — which helps avoid circular discussions later. It’s easier for others to join your reasoning if they can see the path you walked.

When you articulate the expected benefits, you connect the feature to real improvements: fewer steps, fewer errors, saved time, clearer interfaces, smoother workflows. Benefits sharpen the purpose of the request and help the team estimate its value. Humans are inherently motivated by seeing meaning and impact; “this makes life easier in these ways” is far more energizing than “this would be nice to have.” Benefits also help during prioritization, allowing the team to weigh effort against outcome.

No feature exists in a vacuum, and describing risks and dependencies helps the team avoid unpleasant surprises. Maybe the feature touches a fragile part of the system, depends on upcoming work, or introduces edge cases that will require careful handling. Naming these factors up front reduces stress later because it aligns expectations. Teams tend to do their best work when the road ahead is visible, even if it includes obstacles.

Finally, acceptance criteria turn all these intentions into something concrete. They serve as a shared understanding of what “done” means — a checklist that anyone on the team can use to verify the feature behaves as intended. Clear acceptance criteria reduce ambiguity, prevent back-and-forth clarifications, and protect against the common psychological trap of “I thought you meant X.” They also help future teammates (or future you) validate changes long after the feature has been implemented.

Good feature requests do more than describe an idea — they create shared understanding, reduce assumptions, and make collaboration lighter. They remind the team that building software is not just about code, but about aligning perspectives, lowering cognitive load, and supporting each other in making thoughtful decisions.

Skills Shared by All Good Issues¶

- Be specific

- Be readable

- Keep the tone neutral

- Include the details that matter

- Skip the ones that don't

- Write for others, not for yourself

Small habits, big payoff.

Why Templates Exist¶

Templates prevent “Oops, I forgot to mention…” moments.

They help when you're tired, rushed, or juggling five things at once.

Templates support the project's single source of truth

Consistent issues make planning and triage easier and much-much quicker.

Even experienced teams use checklists — not because they’re new, but because they know humans forget things.

Common Beginner Mistakes¶

Feelings instead of facts

“It’s weird” is not a report. Observations are.

Jumping to the solution

Describe the problem first. Let the solution come later.

Skipping steps

Missing preconditions create maximum confusion.

No attachments

A screenshot answers many silent questions.

Blame tone

Bugs are the problem, not teammates.

The Real Payoff¶

Once you get used to writing issues this way:

- bugs get fixed faster

- features get planned more cleanly

- teammates stop guessing

- communication becomes lighter

- the project moves with fewer bumps

Good issues are small investments that pay off repeatedly.

Your future self might even thank you — out loud.